By David R. Wheeler, Editor

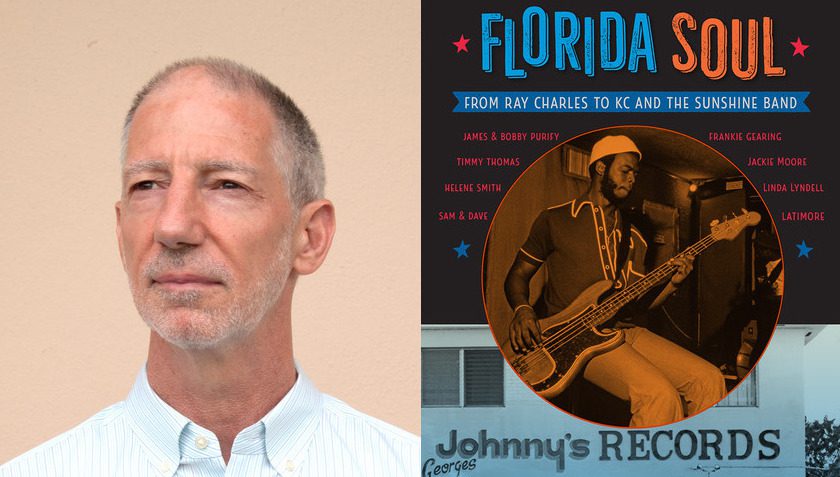

When University of Tampa journalism professor John Capouya heard that the dance craze “The Twist” originated in Tampa, he started to explore the contributions other Florida musicians have made to the genre of soul music. His discoveries set him off on a years-long quest, culminating with the book Florida Soul: From Ray Charles to KC and the Sunshine Band, published in September by University Press of Florida. The book has been not only a critic’s darling, but also an inspiration for many Florida soul musicians to reunite and perform. Publisher’s Weekly describes the book as “entertaining and colorful,” noting that “Capouya’s book assures that the Sunshine State gets its due alongside the musical hubs of Detroit, Memphis, and New Orleans.” Capouya, whom I have the pleasure of teaching with at The University of Tampa, recently sat down with me to discuss his acclaimed book.

ATB: Thanks so much for talking with AliveTampaBay! Let’s start with that little dust-up between Floridian Ray Charles and his rather conservative church. Tell us a little bit about that.

JC: Well, he was a church-going guy for his whole life, but as he said, he’s not a religious guy, just pretty open about a lot of his transgressions. But he was raised in the church and he knew gospel music very well. And one of the things he did — in the beginning of his career — he started out by imitating other artists. He did a great impression of Nat King Cole and an equally great impression of Charles Brown, a West Coast blues singer. And then at one point he realized that he needed to find his own identity. He had some success, because people wanted to hear the latest hit by Nat King Cole, and they were in Florida in some juke joint, and Nat King Cole wasn’t coming there, and they were happy to hear Ray Charles do his version. One of his talents was as a mimic. But at a certain point, he realized that he had to create his own musical identity to do what he wanted to do. And one of the first things he did was he started writing more of his own songs instead of covering other people’s songs, and he took some gospel songs and he transposed them, just changing the lyrics, to be about secular love and singing about her instead of Him, with a capital H. In fact, like one of his big break-out songs was “I Got a Woman Way Over Town Who’s Good To Me.” That comes from a gospel song “I’ve Got a Savior.” So when he did it, people were upset that this sacred music was being turned into “the devil’s music,” as a lot of people saw it. And there was some condemnation of him from the pulpit pretty much across the country. At that point, he had moved to Los Angeles and he was distributed nationally, and so a lot of people heard it and a lot of people didn’t like it. But after a while, the music was so popular and so infectious — and so many people were dancing to it — that basically the church had to stand down. There was nothing they could do about it. And half of them or more were probably going out and dancing to this music on Saturday night anyways.

ATB: Ernie Calhoun called Tampa “the Las Vegas of this area.” What did he mean by that?

JC: He meant it was a kind of an entertainment mecca. In Tampa, in the black neighborhood and Central Avenue, and actually even in St. Pete, when you combine them, it was a huge market, one of the many little stops here on the Chitlin Circuit where black entertainers played for black audiences in the times of segregation. And we also had the Latin invention, the Cuban Patio, which was the patio of the Cuban Club. That was a venue for R&B musicians, also. And all along Central Avenue, there was a whole slew of clubs. There was a Cotton Club, there was a Savoy, and all of these were named after clubs in Harlem in New York. And then in St. Pete, you had another club named after New York called the Manhattan Casino, and that was a very upscale place where big stars like Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald would perform and play. So Ernie Calhoun got a lot of his training, as he explained to me, when he was studying saxophone. He also had a job at a grocery store that was near one of the hotels where touring musicians would stay. So he would make deliveries, and he would add to the delivery a pint of Four Roses whiskey, which would make him welcome. And he would pile on — sometimes he said he would even do it for free. He would just get some bread and some cold cuts and some whiskey and go over to the hotel and see who was in town, and in exchange, he would ask questions, and he would get lessons from these people. It was during one of those times that Percy Mayfield was coming through with a pretty big orchestra. He was a singer and a songwriter best known for his song “Please Send Me Some Love.” At the time, all of this popularity would happen on the R&B charts, and they called them Race Records, so a very segregated black market. If you were black and you were a musician, you could make a good living playing for black people. And so Percy Mayfield heard Ernie Calhoun practicing out the window on Central Avenue. And he had just lost an alto player — or had fired him for not showing up — and he hired Ernie and took him on the road, and that was the beginning of his professional career.

ATB: “Rock and roll” was a euphemism for sex, and as you point out in your book, so was “The Twist.” Tell us how Tampa was the birthplace of this national dance craze.

JC: The urban legend that I started to hear about when I came down here from New York was that “the twist” came from Tampa, and that Hank Ballard, who undisputedly wrote the song and recorded it first, saw teenagers on Central Avenue doing this crazy little dance, swiveling their hips. He asked them, “What are you doing?” And they said, “It’s a little thing we invented that we call the Twist.” He also apparently was given some lyrics by a gospel musician who said, “I can’t do anything with this because it’s about the Twist, which is a euphemism for sex.” So apparently this guy who I interviewed gave him some lyrics and said, “We’ve been fooling around with this song, but we can’t record it, so if you want to, you can.” And so between those two things, Hank Ballard immediately went to Miami and recorded a version of “The Twist” for Henry Stone, who’s sort of like the Barry Gordy of Florida. The guy had a lot of record labels; he was a producer and owner. And then it occurred to Henry that actually he had no business recording Hank Ballard, because Hank Ballard was still under contract to a label in Cincinnati. The guy who owns it would sue him and win, and he’s a very contentious guy named Syd Nathan. So Henry shelved the recording, and then Hank Ballard went back and took his tune to his actual label where he was supposed to record, and he put that out on King Records. And it was a modest hit on the R&B charts. And then Dick Clark, who had his television show, American Bandstand, heard the song and had this young teenager who he renamed Chubby Checker cover the song for another label in Cameo Parkway. Then he invited Chubby Checker onto American Bandstand and everyone in the country saw it, and since it was a great song and a catchy thing and had this crazy dance, it blew up all over the world. So on the 50th anniversary of Chubby Checker’s “Twist” hitting No. 1 on the mainstream Hot 100 pop chart, I investigated this urban legend for the Tampa Bay Times and wrote a piece about it. My conclusion is “The Twist” came from Tampa, and I’m claiming it for my book. And that was the genesis of the book. After that story appeared, I had a conversation with an editor at the University Press of Florida, and she suggested that maybe there would be a book in the history of rhythm and blues in this state.

ATB: As you point out in your book, Chubby Checker’s “Twist” was a note-for-note cover of Hank Ballard’s.

JC: I interviewed him and he was a little sensitive about that. And as he points out, he said, “Look, Elvis covered Big Mama Thornton’s song “Hound Dog” and no one’s mad at him.” I like the way he put it; he said, “Yeah, Hank Ballard wrote it, but I took it to glory.”

ATB: If something is good, if something has staying power, if it can give joy to people, then by definition it must be banned first. Tell us about how “The Twist” was initially banned.

JC: Well, there is this pelvic component, this motion of using your lower body. And it’s sort of like the backlash that Elvis Presley had; people called him Elvis the Pelvis. At one point they would not show him below the waist on television. So I think even more so, strangely perhaps — because this is not a dance in which you touch the other person, so it’s a long way from being an overtly sexual thing — but because of the hip swiveling and the idea that some people were upset, it became popular. Also, it was banned in the Soviet Union for political reasons, because it was an example of Western decadence, and of course, the underground people then wanted to listen to it and dance to it even more. So of all things, the City of Tampa banned its own creation from all of the recreation centers, public centers. They went to the Recreation Director in St. Pete. He was like, “No, hey, we love it. We’re going to twist up one side and down the other.” I don’t know if was ever formally rescinded, but certainly a lot of people were doing it. But Tampa turned on its own.

ATB: Who was the hardest person to track down and interview in person?

JC: I had to find James Purify in prison in California. I knew he was from Pensacola and I was looking for him here, but as it turns out, he was in prison in Northern California. And then, once I found him, I had to jump through a few hoops to be able to interview him. There’s a system by which you can pay for essentially collect calls, so I had to join that service. I found his ex-wife in Pensacola and she was still in touch with him and still on good terms, and she made the request for me. So then he pretty readily said yes, but it did take me some time to ascertain where he was. So what was a person or place that you didn’t realize would be so crucial in helping you write the book, but it turned out to be important?

ATB: What was a person or place that you didn’t realize would be crucial in helping you write this book, but turned out to be crucial?

JC: Well, probably Henry Stone, who was the producer and record label owner in Miami, who I never heard of until I came down here. Even in my initial research, I was just focused on artists — singers and musicians — but as it turns out, Henry Stone is still like the Barry Gordy of Southern Soul, certainly Florida Soul. As it turns out, Henry Stone’s recording career spans approximately 50, maybe 60 years. He kind of bookends the whole book, in that he actually recorded early Ray Charles songs, including “The St. Petersburg Blues.” He was introduced to Ray Charles, who was then going by Ray Charles Robinson. He was at a bar in Overtown, a black neighborhood in Miami, with Sam Cooke. He was recording Sam’s gospel tunes, and Sam introduced him to another singer and said, “I think you might want to record this guy.” Henry Stone says to Ray Charles Robinson, “Oh, you want to make some bread,” as they called it. “Come over tomorrow and we’ll do some tunes.” I was thinking … what if Sam Cooke came, too, and they did some bit together? The talent in this one bar — I don’t know who else was there, but between Sam Cooke and Ray Charles, it was like the roof must have blown off. What if they had sung together? Like Hank Ballard, Ray Charles was doing some recording for Henry Stone that he should not have done, because he was under contract with someone else. But he did, and one of them was called “The St. Petersburg Blues.” So that’s one of the iconic Ray Charles Florida songs. So Henry still had a hand in Ray Charles’ songs, and then he recorded early Sam and Dave, because they formed in Overtown before they went to Stax Records in Memphis and had their huge success. And he recorded several other of the artists, all the way up to K.C. and the Sunshine Band, which is the other kind of chronological bookend of the book. So Henry Stone is involved every step of the way. He recorded Timmy Thomas, who is a chapter in my book. He’s the guy who I had never heard of, who ended up being hugely important. He’s since passed away, but I interviewed him several times. His widow and his son came to my reading, and it was really nice.

ATB: Your book has been well received by everyone. What’s the best compliment you’ve received on the book?

JC: Well, there are two types of compliments or reactions that are important. One is from the artists themselves. I want them to feel that I’ve told their stories well and accurately. And one of them that I was particularly concerned about was this woman named Linda Lyndell, because there were racial aspects to the story that were very sensitive, and in fact, her career, and in some ways her life, was derailed by some experiences that she had that were very traumatic. She did not want to be interviewed in person. She would not be photographed. And it was only when her colleague interceded that she agreed to talk to me. So she liked the story, she thought it was great, she had no problems with it whatsoever. So that was a big relief. Another reaction that I’m proud of was in the Library Journal, which is the magazine that goes to librarians, and it helps them apparently to decide whether or not to buy books. They opened with the sentence that says “Capouya adds a significant entry to the scholarship on soul music with this title.” That was my goal, and if they feel I reached it, then that’s very satisfying. What I thought I could contribute was this notion that Florida actually is a soul capital and deserves to be recognized as such. I wanted to honor some of the individual artists who weren’t famous, but also just to say, “Look, in the aggregate, this is something that’s very important that has been completely overlooked.”