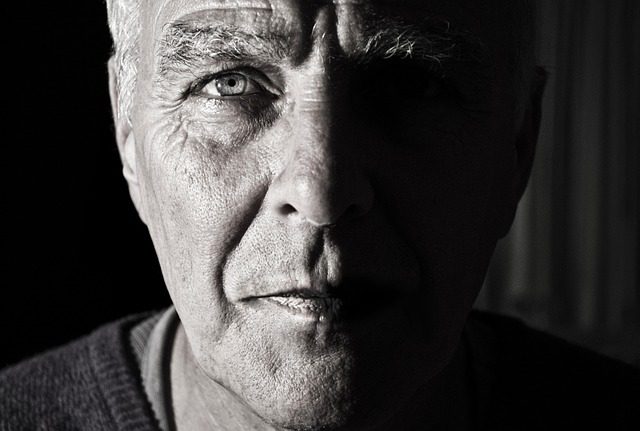

Age related macular degeneration, early stage. It’s progressive. There is no cure.

The nice lady doctor from China or wherever had obviously been trained in breaking such blockbuster news, and the way she delivered it reminded Jerry of how the baristas talk to the customers at Starbucks, so sweet and accommodating, and he wondered whether this doctor had been trained at Starbucks at some time in her life. If so, the training didn’t work. Her put-on sympathy was so strained and false she failed to get him to see any light at all at the end of this very real, darkening tunnel.

“We have treatment, sir,” she said in her high pitched, sing-song English, “No cure yet but maybe not lose all sight, sir. No blind for sure, sir, not like that, sir.”

No blind for sure, sir, not like that, sir. Which to Jerry Thorpe, who had already had more than his share of late life setbacks, meant total darkness, very soon. Christ, it used to be you got old and died. Now you get old and go blind. When did God come up with this new torture?

It was something like the last straw. He wondered whether there was a building he could get to the top of without falling too soon and ending up merely breaking a leg. Only real problem with an early ending to a long tortured existence too full of grief and trauma and hatred and violence in what had somehow become a zero-tolerance world was that such a course seemed like he was copping out, taking the easy path. It wasn’t his way.

“Oh, well, Doc, I hope I can see well enough to find my gun.”

When she didn’t laugh, he knew the joke had fallen flat.

“Oh, sir, please, do not say such things,” she blurted out.

“Don’t worry, it’s not your fault. I’m sure it will be okay.” He tried to cover up his very real angst at the suggestion that he’d soon be blind, but that didn’t work either; it was obvious from the horrified look on her face she remained worried he might blow his head off.

During the next few hours he could not shake the feeling of total loss, complete and utter loss that blindness would mean. His creaking body, painful knees, loss of stamina and mobility, all that was a predictable part of getting old, and more or less tolerable. Blindness on the other hand, to be suddenly thrust into a dark and invisible world, seemed an unbearable burden.

But, if nothing else, Jerry Thorpe saw the bright side of things. A few hours later the panicky feeling had at least temporarily slipped out of his immediate consciousness when there was a knock at the door of his apartment on a quiet, tree-lined street in an old but recovering Tampa neighborhood.

It was a woman, 40-ish, light brown fluffy curls that fell on her shoulders, big smile, Navy trousers very sharply creased, light blue blouse unbuttoned at the top, soft, black walking shoes, extremely non-threatening. He opened the door.

“Hello, sir. You must be Mr. Thorpe?” she said, her voice big and strong, an unexpected volume.

“Yes.”

“My name is Lynette Morino, Mr. Thorpe. How are you feeling?”

“I’m okay, considering,” Jerry said. “Why do you ask?”

“Mr. Thorpe, I’m a police officer.” She opened a wallet and displayed a big gold badge and ID card that announced in tall bold letters that she was from the Tampa Police Department. She let him look at it for a few seconds, then closed the wallet and slipped it in a back pocket. “I’ve been asked to come out and see you because a doctor has reported that you said some things that, well, led her to believe you may harm yourself. I’d like to come in and talk with you. Would that be okay?”

Jesus. What next?

“Listen, officer, you can come in if you want. I was joking. Really, just a joke.”

He stepped back and Officer Morino took a few steps inside. Jerry closed the door behind her.

“Yes, well, she said she’d just given you some news that might have made you depressed. It’s not uncommon for people to feel bad when they hear something like that, then, you know, do something crazy.”

“I can see that,” Jerry said.

Officer Morino’s head snapped around.

“Oh, God, poor choice of words,” Jerry blurted out. “My vision is barely affected at this point. It’s at an early stage. Come in and sit down,” Jerry said, leading her into a room lit by sunlight that streamed in through open, white wooden blinds. “Can I get you a cup of coffee or something? Water?”

“Coffee would be great,” Morino said.

Jerry walked to his kitchen and went to work on the coffee, but he kept his eye on her as she looked around the cozy, cluttered room. Books were everywhere, some arranged neatly on clean but dusty shelves of three different bookcases, all of which he had built out of black walnut, a hardwood easy to work with; more books were stacked in messy piles on a big desk made of white oak, not so easy to work with but very strong. She walked a few steps to the bookshelves and scanned the titles. Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, Great Expectations, In Cold Blood, Herzog. Hundreds of titles, many classics, no bestsellers. She moved to the desk, where there was more of the same. The Sun Also Rises, The Grapes of Wrath, the collected works of William Shakespeare. She ran a hand over the edge of his desktop.

She touched the framed photo of his granddaughter he had taken when she was 6, wearing a knee-high pink dress with tiny ribbons sewed to it making a funny face at the camera, mouth wide open to show perfect white teeth, and another picture of the girl in serious mode, her long blonde braids half way down her back. This cop was making a close inspection of everything.

Jerry ground coffee beans in an electric device and the strong smell of espresso spread through the apartment. He poured water from a tall bottle into the coffee maker and switched it on.

“Smells great, Mr. Thorpe,” Morino said.

“I can’t get enough of this stuff,” Jerry said.

Jerry waited for the coffee to drip into the pot. When the decanter was half full he poured steaming dark coffee into two big blue cups. She walked to an overstuffed red leather sofa and sat on a soft cushion.

“You must love to read,” she said.

“Collected over a lifetime,” he said. “Nowadays, everything is an e-book. No paper, no cover. Just an e-book. I hate it, but it was inevitable I guess.”

“I love my e-books,” she said. “I was looking at your desk. Is it handmade?”

“I built it when I lived in a house with a garage, which was my wood shop. My ex-wife sold all my tools during the divorce, so that was the end of my wood working days.”

“Well, the desk is beautiful, Mr. Thorpe.”

“Thanks. How do you like your coffee, Officer? Milk, sugar, what?” Jerry said from the kitchen.

“Just black,” she said, and she walked back to the couch and sat.

“It’s pretty strong,” Jerry said, and carried the coffee into his living room and put it down on a little glass table that was within her reach. He sat down on an easy chair across from her and cupped the mug in both hands.

“I had no idea the police were so in tune with the community,” Jerry said, a little smile on his lips.

Her eyebrows went up a bit. “When a professional person, like a doctor, calls in a report that there might be a problem, we try to check it out. That’s all.”

Jerry smiled and nodded. There were a few seconds of silence. Morino sipped the coffee then looked at him.

“The doctor mentioned a gun,” Morino said, and put the cup down on the saucer, a nice punctuation mark. Ah, Jerry noticed an urgency in the lady’s eyes that he had not seen before. A gun. They must have worried that once told he would soon be blind, he might kill himself and take a bunch of people with him. So that was motivating this whole deal. An interesting development. What the hell was going on here? He wondered just how much freedom he had left.

“I told you, officer, it was a joke.”

“A joke,” Morino said, nodding. “We were thinking that most people would not be capable of making jokes at such moments, when they get that kind of, what, very ugly news?”

“So you’re thinking, more like a Freudian slip? Like I’m actually planning to blow my head off?”

“It occurred to us, Mr. Thorpe. I admit, it occurred to us, or I would not be here.”

“Us. Who’s us?” Thorpe said.

“At the Department, the Tampa Police Department, we have experience in these matters. It’s a different world, Mr. Thorpe. We worry about a lot of stuff now we didn’t just a few years back.”

Jerry sipped his coffee, looking straight at her.

“You think I might take others with me? Is that it? You suspect I’m capable of mass murder?” Morino tensed, straightened her fingers. She was ready. Ready for him to whip out a Glock from a hidden holster and let her have it. She wasn’t taking chances.

“We don’t suspect anything at this point, Mr. Thorpe. Right now we’re concerned about your safety.”

“I’m licensed to carry a concealed weapon.” Jerry said the words slowly, deliberately.

She did not flinch.

“I know, we checked.”

“Jesus,” Jerry said, sitting up in his chair. “You guys don’t miss a beat, do you? And you work so damn fast.”

“It makes sense, doesn’t it? To check? And if something’s going to happen, it might just happen quickly, so we’ve got to be quick, too,” she said.

“You have a lovely smile. And I suppose the soft curls and civvies are supposed to keep me at ease, right? Don’t agitate the crazy old bastard? Is that it?” Jerry said.

She laughed out loud.

“You’re very perceptive, Mr. Thorpe. Very perceptive.”

They were quiet for a few seconds and the tension seemed to have eased. But she wasn’t finished with him.

“Besides this eye disease, which I am told is treatable, Mr. Thorpe, are there other things?”

Other things. Suddenly the Police “concern for his safety” had taken an odd twist, hadn’t it? Just how much of Jerry Thorpe’s life had come under scrutiny? Just how much did they know and what else might be on their minds?

“Aren’t there always other things, Officer? I’m wondering, do you already know about them?”

She looked around the living room, took a breath, her very dark, almost black eyes came back to his.

“We are aware you were in a custody dispute with your daughter over her child, your granddaughter. You went to court.”

“That record was supposed to be sealed,” Jerry said. “Records of the dependency court are not open to the public.”

“Correct,” she said, her head dropping. “The police department is not the public.”

Jerry nodded.

“You know what happened? You know the whole story?”

“We know she left the child with you for four years. We know she was taking drugs and unemployed during that time and could not care for the child and most likely was living on the street. We know she came back after four years and took the child from you, which you contested in court. Your position was it was not in the best interests of the child to be taken from you after you cared for her for four years.”

Jerry nodded. “Do you know that when she came back after all that time she was still using drugs? And she was living with a drug dealer. Did you know that?”

“We know that’s what you told the Department of Children and Families at the time. We know they said the evidence was insufficient to keep her from having custody of the child. That was their ruling.”

“Their ruling,” Jerry sneered. “Do you know where that child is now?”

“I do not,” Morino said.

“Neither do I,” Jerry said, waving a hand. “But I would not be surprised if she’s living in a drug house in the middle of a drug neighborhood in the middle of a drug deal and maybe shot up with drugs herself. She’s only seven, Officer. She’s out there in the middle of a drug-addicted world and I can’t do a goddamn thing about it.”

Morino nodded. A few seconds passed. “Is that her picture on the desk?”

“Yes,” Jerry said.

“She’s beautiful.”

“Yes,” Jerry said. “She is.” He stood up.

“So you’re thinking that I might use that gun to fix the situation with my daughter? Is that it? You think I might be capable of that? Is that your suspicion, officer?”

“I told you, we have no specific suspicion at this time. We’re just…we’re just asking questions.”

“You brought up my granddaughter for a reason. You know about it and you brought it up and you’re here, so you must be thinking about it.” Jerry was getting agitated. But she was watching his every move, so he kept it under control.

“And the goddamn court and the goddamn government can’t protect that child at all, can they? What the hell do you call that?” Jerry said.

Morino did not answer. She looked away from him then, across the room and out the window. Jerry followed her gaze and saw a police car parked at the curb.

“Is that your police car?” Jerry said, gesturing out the window.

“No,” Morino said softly. “It’s a back-up unit and he’s not supposed to be where you can see him. So. Great. We screwed that up pretty well.”

They both laughed out loud. Then Jerry became serious again.

“Do they have a gun on me from out there? Is there a sniper?”

Morino turned her head and looked out the window again.

“I don’t know for sure. Maybe. Probably,” she said.

“Jesus,” Jerry said. “All for some guy going blind.” He shook his head. “What else? What else do you know about?”

Morino’s shoulders pushed back in the couch and she looked at the ceiling for a second, then came back to Jerry.

“We know you were in the Marines. We know you served in Vietnam. We know you were nominated for a bronze star. Good conduct medal. We know you were an expert rifleman, qualified on the M-1, M-14, and M-16 rifles, the Colt .45 hand gun, and also were trained on all weapons in use at the time, including the M-60 machine gun, the 104 millimeter recoilless rifle, M-26 fragmentation grenade, flame thrower, 3.5-inch rocket launcher and trained in the preparation and use of Composition B explosives and fuses.”

Jerry nodded. “You left out mines. Your ever hear of a Claymore? It blows you up when you trip a wire. I can set up a mine that will blow you to smithereens when you open the door to your house.”

Morino sat up straight and looked at him.

“I was also taught how to kill people with my hands. Just my hands. Did you know that?”

“No, Mr. Thorpe. We didn’t know that.”

“That’s because they didn’t put everything in the service record. You’ve looked at my service record but you didn’t go back and talk to Gunny Howell or Gunny Cass or Sergeant Berndt or anybody else who was with me in Vietnam. They could have told you some other stuff about me, not very nice stuff. It was a war, Officer. You had to survive. A lot of people did not. I was lucky.”

She nodded.

“What else you know about me, Officer? Anything else?”

“We know your mother died when you were five,” she said.

Jerry’s head snapped around.

“How the hell did you know that? What the hell is this, some kind of witch hunt?”

“It’s a matter of public record, Mr. Thorpe, your mother died in an accident when you were five years old. It’s no witch hunt. We did a little research, that’s all.”

“A little research? Did you find out that she was nine months pregnant at the time? That she fell down on a sidewalk so they took her to a hospital and the wise and educated doctors thought she had gone into labor and so they put her in what was called a labor room? But she hadn’t gone into labor. What happened was she had a ruptured spleen, and the wise and educated doctors let her lie back there in that labor room until she bled to death. Was that in the record?”

Morino shook her head. “I’m so sorry, Mr. Thorpe. No, we didn’t find that.”

He waved one hand. “Don’t be sorry for me,” he said. “I was five, I hardly knew her. But my sister, she was 15. It damn near killed her. She’s never been the same.” He took a breath, He came back to Morino. “It sounds to me like you did more than a little research. Sounds like you sliced me open like a fish,” Jerry was pacing again. She kept her eye on him every second. She remained at the ready, and he was now sure a sniper had him in the sights of a high powered rifle.

“So does growing up without a mother make a person a killer?”

“No, Mr. Thorpe, it does not.” She set her jaw.

“And my divorces. You obviously know I’ve been divorced twice.”

“Yes. And you have two children.”

Jerry nodded. “Did you know that my second ex-wife, Joan, had an abortion against my wishes? Did you know that? That she killed my child for no good reason? I begged her to please not take that life. Didn’t matter. After all these years of reflection, I’m convinced she did it just to get at me, just to show me she was in charge.”

There was silence in the room for a long time, maybe a minute. Finally, Morino said, “We didn’t know about that, no.”

“Well there it is. It was nothing to her. An hour or two in the hospital. Nothing to it. Vacuum out your baby and wash it down the drain. You didn’t know about that, huh? Well, take it back to your intelligence squad. Something for their files. If they ever want to investigate a killer, go check out my ex-wife. All perfectly legal. Shit, officer, I drove her to the hospital the day it was done. Can you believe that? Because I couldn’t convince her otherwise. I had to take care of the two children we already had. I couldn’t leave her. I wish to God I could have.”

Morino was moving around in the chair, shifting her weight. It looked to Jerry like she was a little more nervous now because of that last rant, but still hanging in there, looking him over the whole time. He kept pacing, but kept his eye on her, looking for reactions, any jerky movements for that gun he knew damn well she was carrying somewhere on her body.

“Officer Morino, are you carrying a gun?”

She looked at him. “I’m not supposed to give you that information, Mr. Thorpe. In this situation, you’re not supposed to know.”

“Really? Well, I’d like to know, just for my own comfort level, if you’ve got the ability to kill me right here and now. I have not done a goddamn thing to warrant you even being here, sitting in my living room questioning me, and damn sure nothing to have some goddamn sniper aiming at me, so I’d like to know.”

She took in a deep breath and let it out. “Okay. I’ll break the rules. Yes, I’m carrying.”

“Thank you. Thank you for sharing, Officer.”

They were silent for a few seconds. Jerry went to the kitchen and poured more coffee in his cup.

“Refill, Officer?”

“Sure,” she said. Jerry brought the pot to her and poured steaming hot coffee in her cup. He turned to go back to the kitchen.

“And your gun? Are you carrying it, Mr. Thorpe? I’d just like to know,” Morino said.

He put the pot down, turned and looked at her. He waved one hand. He saw no reason to keep it from her after all that had been said.

“Yes, Officer, I am. A Colt .45. It’s called a Combat Elite. Fancy name, but it’s basically the same gun I carried on guard duty, what, 30 years ago? It’s in an ankle holster and I’ll let you see it if you want. Nice weapon, very reliable. I’m not carrying my M-16. It’s also the same weapon I carried in Vietnam. Very light, very nice weapon. It’s locked up in my bedroom. I’ll let you see it, too, if you want.”

She nodded. “I don’t need to see them, Mr. Thorpe. I believe you. Does having the guns makes you feel safe?”

“Well, look at this. I’ve got a .45 on my ankle, but you’ve got a sharpshooter out there with a high powered rifle and you’re sitting five feet away with something powerful on your belt. So, no, Officer, I’m not really feeling that safe right now. I can’t get him but he can almost certainly get me. My M-16 has an effective range of 500 meters, and I bet he’s got a better weapon than that, so I’m well within the range of his rifle, but I can’t even see him, so no, I’m not feeling real secure sitting here in my airy living room with all these windows. No place to hide.”

She smiled. “There’s certainly nothing wrong with your mental acuity, Mr. Thorpe.”

“No, I guess I haven’t lost my mind, yet, although that’s probably next,” he said.

They both smiled at that.

Her hard black eyes grew serious again: she had more.

“There’s one other thing in your service record,” she said, stretching her legs. “Temporary duty with Air America.”

Jerry smiled, took a breath. Neither of them spoke for a long time.

Finally, Jerry said, “I’m afraid I’m not allowed to talk about that, Officer. And I suggest you be very careful about poking around in it.”

“Mr. Thorpe, we know very well Air America was an operation carried on by the Central Intelligence Agency in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand during the time you were there. Spies, Mr. Thorpe. It was a secret then, but it’s not anymore. Obviously, people were killed. That much is public knowledge.”

“That’s fine,” Jerry said. He had suspected this would come up. He was confident about how to handle it. “I will refuse to talk about anything that had to do with Air America and if questioned further, I will call a person in the government, in Washington, D. C., who will tell you and your chief of police and your mayor and whoever the hell pays your salary that they had better goddamn well mind their own business and quit poking around in highly classified matters of national security. You may think you know what’s public and what’s still classified, but you may not. Those people, they don’t like it when somebody starts poking around in secret stuff.”

If she was fazed by this thinly veiled threat, she didn’t show it. But she didn’t come back to it, either. Was that a surrender?

She looked through the hallway and out a side window. A wide 18-wheeler rumbled past on the narrow road, fallen leaves rushing up in its wake, the roar of its diesel engine a loud intrusion on the quiet neighborhood. She came back to Jerry.

“We know your father had what was referred to in those days as a nervous breakdown. He was hospitalized.”

“Oh, so you’re worried I might have inherited some mental defect, is that it?”

She shrugged. “It was in the record. Have you had any mental problems, Mr. Thorpe?”

He looked at her.

“Not yet, officer.” He shook his head. “The thing with my father was before I was born. Nobody made much of it. He always seemed rock solid to me,” Jerry said.

“After your mother died he had several affairs, yes?”

“God,” Jerry said. “How the hell do you know about that?”

“One of them was a married woman whose husband, when he found out about his wife and your father, he bought a gun and came after your father. It was reported to the police.”

“God, I did not know about that,” Jerry said, genuinely surprised. He turned to face her. “Well, let me change that. I did know about the woman, sure. She was at my house all the time. But I didn’t know her husband came after my father with a gun. I never knew that. What happened?”

“Your father, it seems, was very ingenious. He managed to disarm the man and basically walked away from the man’s wife, so it ended.”

“No kidding? God. Joanne Rickover, right?”

“Yes,” Morino said, nodding. “You knew her?”

“I told you I did. I knew all about the affair. We lived in a big house and my bedroom was upstairs. I could hear them going at it in the bedroom downstairs. One time I sneaked down and watched them, you know, having sex. I was what, maybe 11 or 12 at the time. Jesus. What a show.”

Morino shook her head.

“Of course we didn’t know about that.”

“You didn’t have a camera in my father’s bedroom?”

“No,”Morino said, laughing. “No camera in the bedroom.”

Jerry waved a hand.

“So you also didn’t know my father had a temper. Once after my mother died, he bought brand new living room furniture for the house we lived in. Beautiful stuff. I remember it like it was yesterday. Dark wood, walnut I think. Early American. Had all these weaving wheels, or, what do you call them? Spinning wheels I guess, log cabins and other things the settlers had, I guess, printed on the fabric. Well, my sister, she was 10 years older than me, she accused him of buying the furniture so he could ‘bring women into the house.’ My sister tells him this. I’ll never forget it. He went nuts. With his bare hands he broke that furniture into tiny little pieces. Snapping wood like it was nothing. Bare hands. He was strong as an ox, my father. The whole time he’s screaming, ‘Bring women, huh? I’ll show you about bringing woman.’ And he breaks this stuff up into little pieces.”

“You watched him?”

“From under the kitchen table,” Jerry said.

“Jesus, Mr. Thorpe. “What about you, Mr. Thorpe? Do you have a temper?”

He considered the question for a few seconds. “I have always found that getting angry hurts me more than it does whoever the hell I’m angry at, so I try to think about that before going off halfcocked.”

“Good policy,” Morino said. “My father had a temper, too.”

“Did he ever break up any furniture?” Jerry said.

“No,” Morino said, shaking her head. “But he beat the hell out of my mother.”

“That’s not good,” Jerry said. “Did he hit you, too?”

“Oh, yeah. But you know, in the old days, it was more or less accepted to hit the kids.”

“Things have changed for the better on that score, Officer.”

She shrugged.

“I suppose. Although, sometimes I think my 14-year-old daughter could use a shot in the chops. She’s got a mouth on her,” Morino said.

“She have a father?”

“Ha,” Morino let out a laugh. “That bastard. All he’s good for is… nothing. He’s good for nothing.”

“Divorced?”

“Never married,” Moreno said. “Just a bad choice. I should have never gotten involved.”

“Yeah, but, then no kid,” Jerry said. “You wouldn’t go back on that, would you?”

“No,” Morino shot back. “I wouldn’t. She’s my baby, but she’s at an age when, she’s challenging. She’s got hormones. They’re driving her.”

“Hormones. You believe in God, Officer?”

She looked at him oddly, “God? What’s he got to do with it?”

“You can blame God for the hormones. Excuse the expression, but you don’t want to be blind to the cause of things. Sex, it was like the first thing there was, maybe only food would have come before sex,” Jerry said. “So of course she has hormones. It’s God’s plan.”

They were silent for a while. Finally, Morino stood up.

“Mr. Thorpe, I don’t think you’re a danger to yourself, not today anyway.”

“Oh, good,” Jerry said. “I’m so glad.”

“Yeah, me too. Because if I did, we would have had to Baker Act you. That means, put you in a hospital for observation.”

“Really? And what qualifies you to make that decision, if you don’t mind me asking.”

“I don’t mind you asking,” Morino said. “But the answer is nothing. The Baker Act law simply says law enforcement officers have the right to have people held against their will and evaluated if they have probable cause to believe they are a danger to themselves or others. You tell a doctor you want to be able to find a gun right after she told you what she told you is just about good enough. She didn’t think it was a joke.”

“She was a Chinese lady, or some kind of foreigner. People from other countries, they don’t understand the American sense of humor. They don’t get it,” Jerry said.

Morino shrugged. “Maybe,” she said.

Jerry said, “So the way you and your buddies down at the police station decided to check me out was to have a nice looking woman in civilian clothes knock on the door and have a talk and share family secrets and see what you think?”

“That’s about it.”

“Damn,” Jerry said. “And the sniper?”

“Just a precaution. In case things went, you know, bad.”

She walked toward the door and Jerry opened it for her.

“And if you would have Baker Acted me, there would have been handcuffs?”

She nodded.

“For the transportation, sure. It’s the protocol whenever we transport,” she said.

Jerry took a breath.

“That’s something we didn’t have to worry about in Vietnam,” he said.

“No handcuffs?”

“No prisoners,” he said.

“Ah,” she said. “I see.”

“It was nice talking to you, Officer.”

“I hope I wasn’t too much trouble,” Morino said. “If the blindness thing starts to get at you, give me a call,” she said, and handed him a business card with her number on it.

“Thanks,” Jerry said. “I’ll think about that. And listen, don’t hit the kid. There’s a better way.”

Morino nodded. “I’ll try to remember that next time she calls me a slut pig.”

“Hmmm. She calls you that?”

“Whenever she wants to get on my nerves.”

“Damn spunky kid,” Jerry said. “You know, the way you’re talking, you might be a candidate for a Baker Act yourself. You said harm to others qualifies, right?”

“Yes, it does.”

“Well, you might be a danger to that kid. You said she needs a ‘shot in the chops,’ I think is the way you put it. Can you Baker Act yourself?”

“I never thought about it before,” Morino said. “I’ll keep it mind.”

“And the father. I hope he doesn’t come around looking for more time with your daughter. You might decide he needs a ‘shot in the chops,’ or something more severe. So remember the Baker Act, Officer.”

“All right, all right. I get it. See you later.”

“Make sure you get that goddamn sniper out of here. I don’t want to say anything that might get me Baker Acted, or shot.”

“Good plan,” Morino said, and got in her unmarked car and drove away.

Joe Registrato is editor of AliveTampaBay.